Food security is a topic that Australians might more readily associate with developing nations in famine or suffering food crises.

However, food security is a very real issue in Australia – regarding current rates of obesity, diabetes and access to affordable and healthy food, and, into the future as our climate changes and our population grows.

What do we mean by ‘food security’?

Food security is defined by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation as being access by all people to sufficient, safe and nutritious food. That is: food is available, accessible and our bodies are healthy enough to utilise the nutrients in food. ‘Access’ refers to:

- physical access: being easily able to reach a market or source of food

- economic access: that safe and nutritious food is affordable

- social access: people’s access to food is not restricted by their social status or class.

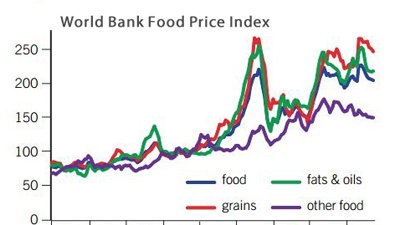

Food security is increasingly threatened by price rises in inputs to agriculture, such as fossil fuels and fertilisers, which lead to food price increases. Between 2002 and mid-2008, global food prices increased by 64% (FAO 2008), reducing many people’s capacity to purchase sufficient healthy food to feed themselves and their families.

If there was a disruption to Sydney’s main transport route (from bushfires, fuel supply disruption or other) –Sydney’s fresh food reserves are estimated to be only a few days’ worth of supply

Further, the price of food in Australia is relatively high, meaning that although Australia produces enough food to feed our population, not all Australians are able to access it. Almost 20% of the Australian population are welfare dependent and could not afford to purchase fresh, healthy food (Kettings et al. 2009). Even within the City of Sydney, some households with children and many government‐assisted households will be experiencing or approaching food stress. For example, many government‐assisted households are spending a third of their incomes on food.

Food waste and spoilage must also be taken into account – indeed, the amount of food consumed is significantly lower than the amount of food produced (see section on Food Waste below).

As our climate changes, the vulnerability of our food system will increase, making it more susceptible to shocks. In 2009, a winter heatwave destroyed south-east Queensland’s wheat crop, costing most than $150 million in lost income and commodities. As our climate changes, we can expect these disasters to occur more frequently and with greater intensity, at the same time as Australia’s food system is required to feed a growing population.

Farming is also becoming less profitable in Australia, resulting in a decline in the number of farms and farmers currently operating in Australia. Australia-wide, farm numbers decreased by approximately 10,000 in the decade to 2009 (ABS, 2010). Generally, farms have been forced to grow to a larger scale in order to remain profitable.

Agriculture in peri-urban areas of our cities represents a small but vital component of our food system and economy. As Australia’s rural food production becomes increasingly vulnerable to climate change, peri-urban regions may grow in importance.

Food production close to metropolitan areas also plays an important role in food security in that it removes some of the risks associated with transporting food over long distances. Food transported over great distances is vulnerable to spoilage, more likely to be enhanced using preservatives and colours, is exposed to price fluctuations due to reliance on fossil fuels, and is more likely to be expensive than food produced locally (Paul and Haslam McKenzie 2011).

In order to create a sustainable city it is essential that a substantial amount of production takes place in close proximity to the consumer to ensure freshness, reduce carbon footprint and increase agricultural output.

If there was a disruption to Sydney’s main transport route (from bushfires, fuel supply disruption or other) –Sydney’s fresh food reserves are estimated to last only a few days based on the throughput of the Sydney Flemington Market. Changing trends in food demands, having a competitive advantage over other products because of their freshness, locally grown and no food miles involved.

Not only are meat-heavy diets linked with these health issues, but they are also likely to be more environmentally harmful, and use much more water, energy, fertilisers and land than would be required to feed the same number of people with a plant-based diet. In 2006, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation reported that 30% of the Earth’s total land mass is devoted to feeding and raising livestock. A study in the US (Kreith, 1991) found that producing a pound of beef requires between 50 and 100 times more water than an equivalent weight of fresh fruit or vegetables, such as oranges, tomatoes, lettuce or broccoli. Further, to produce one calorie of meat-based protein consumed around ten times the amount of fossil fuels as to produce one calorie of plant-based protein (Pimentel, 2003). A meat-based diet an also require 2-3 times more finite phosphate fertiliser than a plant-based diet. Meat-based diets also have a greater climate change impact. It is estimated that 18% of human sources of climate change are due to livestock production (FAO).

Australians throw away around 40% of all food grown – a grocery bill worth $5.2 billion a year, more than the annual cost of running the Australian Army ($4.8 billion)

Food waste is a major issue that may compromise Australia’s food security in future. Although Australia produces more than enough food to feed its population, much of this is not eaten, but is thrown away.

Australians are throwing away around 40% of all food grown – a grocery bill worth $5.2 billion a year, more than the annual cost of running the Australian Army ($4.8 billion) (Baker, Fear, and Denniss, 2009). The University of Western Sydney estimates that the $1 billion worth of edible food thrown away each year by Sydney’s households is equivalent to the income of all farmers in the Sydney Basin.

Food waste occurs at several points within the food system, from paddock to plate:

- There is a proportion of produce that never makes it beyond the farm gate, due to spoilage, below-cost prices offered and supermarket standards, which demand unblemished produce.

- Food is wasted in processing, when fresh food is processed, packaged or treated in factories and transported.

- Food is wasted in markets and supermarkets, which commonly over stock shelves, dispose of products that do not meet standards, and which dispose of food with blemishes, such as stonefruit with hail marks or cans with dents.

- Food is wasted by households, restaurants and other food outlets, due to poor planning and overstocking, larger-than-needed portion sizes, and by a failure to consume food before it expires.

Globally, food waste is an enormous issue. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations calculates that 1.4 billion hectares of land is used to grow food that is never eaten, and that around 1.3 billion tonnes of edible food are discarded each year. Estimates vary, but it is thought that 30-40% of all food produced global is never consumed.

It is estimated that 5.25 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions are caused by household food waste decomposing in landfill in Australia

This food waste is largely sent to landfill, where the decomposition of organic matter emits greenhouse gases. The decomposition of organic waste, such as food waste, is the main source of the greenhouse gas emissions that arise from landfill. It is estimated that 5.25 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions are caused by household food waste decomposing in landfill in Australia – a rate of pollution that is similar to the total emissions involved in the Australia’s manufacture and supply of iron and steel (Burns et al., 2011)

If Australia minimised its wastage of food, it would be able to feed many more people at the same levels of production that occur today.

Turning waste into opportunity

Innovative non-profit organisations like OzHarvest and SecondBite seek to reduce and redistribute wasted edible food to vulnerable people in Australia. Together they have diverted over 26,000 tonnes of food from landfill, which enabled them to serve over 60 million meals to over 1,700 charities and community food programs. In France, new legislation is banning supermarkets from throwing out edible food, in a move to tackle the coupled food waste and food poverty epidemic.

Food waste that is inedible, like egg shells and banana peels, can be composted with other organic and green waste from the city to reuse as fertiliser and soil improvements. Social enterprises like Green Connect compost Sydney’s food waste for use in their farm in the Illawarra region, which employs former refugees and young people to grow fresh, seasonal, chemical-free food for the region.